The Angel, the Automobilist, and Eighteen Others

What Would Prince Edward Think?

40 pages

7.5 x 6 inches

Smyth-sewn casebound hardcover,

with dust jacket

ISBN 9780764975400

$13.95

For more information visit Pomegranate's page.

Reviewed by Glen Emil,

copyright 2020 Goreyography

At times, I can see why procrastination works to my advantage. It provides a void, a space for things to happen. This time, two events, two disparate occurences came together to create a special moment. Had I acted promptly, without delay, they would be just two separate events. Now, it's the nexus of how a lasting memory was formed.

A month or two ago, Pomegranate released The Angel, the Automobilist and Eighteen Others, a new, posthumous 'book' by Edward Gorey. It was a long time coming. Attendees of the 2016 exhibition at the Edward Gorey House museum may remember selected artwork from The Angel, the Automobilist and Eighteen Others on display, along with the announcement of its publication later that year. Finally it arrives, years later. I located my digitally buried notes and began research for a review of this much-anticipated early work. But something important was missing: my scribbled notes from conversations with Andreas Brown about the work's discovery in the Gorey archives some years earlier. I began reaching out to Mr. Brown, to clarify what he'd said about the book a few years earlier.

Before we had a chance to speak, on a chilly March 6, I received news that Andreas Brown had passed away, in New York earlier that day. He was 86 years old. I was stunned. The voicemail messages to my old friend will go unanswered, forever. The press will no doubt remember Andreas Brown as the owner of that venerable literary landmark The Gotham Book Mart in Manhattan, after its founder Francis Steloff retired. As for myself and the Edward Gorey collecting community, Brown was the gateway to Gorey heaven; for most of us the two became inseparable. One couldn't get to Gorey without going through Brown. He was the printer of price lists, bringer of news, deliverer of precious books, and buyer of retired collections. Celebrities and students were at his fingertips, lists of which he kept very close to his chest. Even after Gorey died in 2000, Brown kept him alive, for hundreds of Gorey fans (and for grateful booksellers).

Brown was a fountain of information, both about Gorey and the details about most of Gorey's books as they came to press after 1968. He also very much looked up to Gorey, for his obvious artistic talent but mostly for his deep thinking. He often tried to 'decode' Gorey's works. Brown felt that Gorey always placed hidden meaning in this little narratives, yet was always rebuffed by Gorey when he attempted to do so. "What you see is what you get" was Gorey's most-used response. I remember how excited Brown had been when he talked about finally publishing The Angel, the Automobilist and Eighteen Others, and what he began considering as Gorey's first 'book'. Fittingly, it turns out to be the last book he posthumously published for Mr. Gorey. Bookends to a career, maybe two.

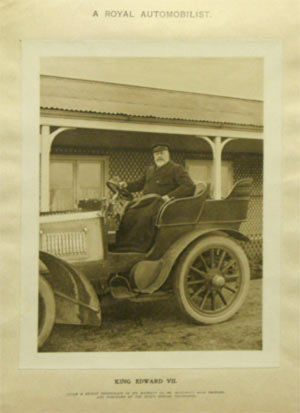

Brown was a fast talker, so I could only take rough notes during our discussions of The Angel, the Automobilist at the Gorey House, and from a subsequent phone conversation. I've patched together what I could. Brown considered that The Angel, the Automobilist was either a) an incomplete or abandoned book, most likely predating Gorey's first book 'The Unstrung Harp' in 1953, or b) part of a portfolio of 'works-in-progress' to show prospective publishers. He further speculated that the common theme of the artwork as a whole was tied to the life of King Edward VII, recalling a photograph of the King sitting in one of his automobiles, titled 'The Royal Automobilist', dated 1902. Brown had said he found quite a few parallels between events during the monarch's history and the illustrations he uncovered. Unfortunately, our discussion was interrupted, and ended there. Following the same path, I try to pick up where Brown left off, offering many of them at the end of this article.

Have a look below at what's behind The Angel, the Automobilist, and Eighteen Others.

When asked why he didn't publish this group of illustrations in Amphigorey Again (2006), Brown said he wasn't yet comfortable considering The Angel, the Automobilist a completed work, since there were only seventeen 'others', not eighteen as the title maintains, and he hadn't found any notes Gorey typically made when producing a stand-alone book. He even questioned whether it was meant to be published at all. He later changed his mind, thinking that it was a valuable contribution to Gorey's oeuvre. As for the Trust's plan to publish it in 2016, differences of artistic opinion between Brown and the publisher, delayed it to 2020.

The manner in which Gorey portrays Edwardian English life is often the most entertaining aspect of his books. While the Great Britain he revisits is indeed a society secure in proprieties and prim refinement, it's bowels are swollen with nameless conflicts, of cruelties facing the young and innocent, of injustices at the hand of tyrannical businessmen, perverse clergymen and loose masonry. Beneath his cold, imperfect facade breathes souls gripped by repressed inhibitions and ambitions. Within these ranks we find dramatic players, both real and created, who left their mark by living life to the hilt, come what may, as comedic (or tragic) prima donna and primo uomo of their era. In true operatic fashion, Prince Edward and the leading ladies of his day certainly lived life as if it was indeed their grand stage. In The Angel, the Automobilist, and Eighteen Others, Gorey didn't so much invent caricatures, but had only to illustrate them as they presented themselves to a bewildered public.

Looking at The Angel, the Automobilist and Eighteen Others through these lens, a loosely bound narrative appears, as things do in a picture album. It then begs the question of why Gorey focused so keenly on King Edward VII in the first place. Was it the spectacle of Prince Edward's raw pursuit of pleasure, nearly crippling the British monarchy along the way, only to be celebrated as an effervescent, brilliant and beloved monarch by the time his death in 1910? It's certainly a story worth recounting, if that be the case. English society at the turn of the 20th century was bold, pretentious, and unapologetic, with loads of drama gripping the royal families of Europe as a backdrop. A flawed, all-too-human Sybarite, bound alongside an uncompromising royal family and a conservative English culture, was a factory of cautionary tales in the making.

Gorey's portrait album seems at first cryptic, even entertaining, as it captures vulnerable and even heartwarming moments. If they portray real players, in a real drama, then it excels. A young Edward Gorey, maybe 25 or 26 at the time, was still honing his craft, delivering this little bit of British history so naturally, early on in his career. This colorful bit of human history, which Andreas Brown believed, as now do I, is what Gorey masterfully pays homage to, in all his black and white simplicity.

Thank you, Mr. Brown. You have given all of us much to think about.

What's behind The Angel, the Automobilist, and Eighteen Others.

Trying to pick up where Brown left off, I've put forward the many parallels drawn between Gorey's illustrations and instances which defined King Edward VII's life. Some of the speculation or conjecture read into the illustrations were Brown's, many are my own, but by and large reflect what Brown and I talked about, and what I was able to corroborate. I only wish now we had a chance to compare notes.

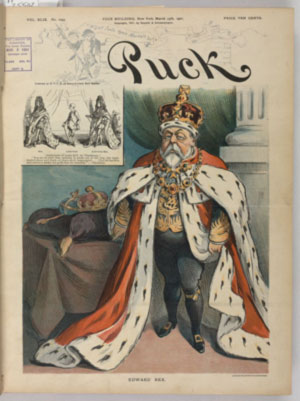

The cover illustration: depicting Prince Edward Albert, the Prince of Wales, just prior to his accession to the throne as King Edward VII, in coronation garb. This illustration seems based on the cover of Puck magazine's March 13, 1901 issue, seen below. In Gorey's version His Royal Highness, longingly gazes at an autocar, and seems to realize the days (read years) of freedom, sometimes bordering on wild abandon, are coming to a close. The angel of investiture hovers above, bearing Britain's heavy crown, and appears as uncertain as Edward.

The Angel: (speculation) The Angel carries a watch signifying Queen Victoria's death, now on his way to Edward Albert, Prince of Wales, who is now to be crowned King of England. Uncertainty registers on his face. Alternatively, King Edward's connection between Cartier the jeweler and celebrity balloonist and aviation pioneer from Brazil, Alberto Santos-Dumont, directly led to the popularity of the modern wrist watch, and to the demise of the pocket watch, in men's fashion (also see The Balloonist).

The Automobilist: Edward, Prince of Wales, regards a memorial of his late father, Prince Albert, Queen Victoria's husband, after his death in 1861.

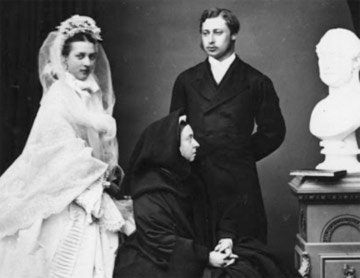

For decades the Prince waited for the day he would assume the throne. Until then Edward, or 'Bertie' to his family, lived in the shadows of his royal parents, filling his waiting years with what can only be described as 'the high life' of cars, ladies, horses, parties, et al. The Queen regards Bertie's wild and debauched lifestyle with sharp disdain, and ultimately blames her husband Prince Albert's untimely death in 1861 on her 'frivolous, indiscreet and irresponsible' son Edward. An official family wedding portrait taken before Edward's marriage to Princess Alexandra shows a large bust of the late Prince Albert, standing right beside Prince Edward, as a reminder from his mother.

The Artist: Gorey caricatures himself, as a satirical chronicler of events, with his initials on paper and inkwell resting upon a baluster.

The Oboist: correlation undiscovered.

The Explorer: Captain Robert Falson Scott leads the Discovery Expedition, Britain's first major scientific exploration of Antartica. It was a highly successful and popular expedition, with unclaimed regions of Antartica named King Edward VII Land in 1902. The King visited the RRS Discovery before her departure, and the crew commemorated his 61st birthday with sport during their long stay. Though Edward travelled extensively before and after his accession, he had not personally visited the Antartic.

The Wretch: Queen Victoria and the royal family must bear the disgrace of Edward, Prince of Wale's wreckless behavior, often leaked and sensationalized by the press. Bertie's exploites strengthened the growing anti-monarchy republican movement, and his mother punishes Bertie by further separating him from official royal affairs, and begins to despise him personally. Princess Alexandra, Bertie's wife, however, seemed to accept his many mistresses as part of their marriage.

The Doubleganger (doppleganger?): (speculation) Edward, Prince of Wales's incompatible dual personalities: a dignified royal and spiritually corrupt playboy. Alternatively, and also literally, an attempt upon Edward's life and his mother Queen Victoria's survival of no less than eight assassination attempts avails the royal security detail the use of body doubles in public appearances.

The Suicide: correlation undiscovered.

The Ennuye: Bertie, as Prince of Wales, waiting in limbo, has feelings of insignificance, boredom, weariness and dissatisfaction during his decades-long wait to assume the throne. Edward was the eldest royal sibling, and had ambitions to match. For forty years, they remained unfulfilled. He counters this by diving head first into high society, parties, horses, Parisian brothels and billiards. He made sure his residence in Sandringham House had very grand billiards rooms.

The Balloonist: (speculation) Edward supported the famous international balloonist Alberto Santos-Dumont of Brazil, a high-flying celebrity in Europe at the turn of the century, and who was the center of controversy when he was suspected of sabotaging his own airship balloon before a famous balloon race in London, in 1904.

The Agent: (speculation) Possibly foreign spies working against the British royal family, in connection with the previously mentioned assassination attempts.

Here, direct connections to other Gorey books appear: in The Unstrung Harp (1953) as worn travel posters promoting NETHER MILLSTONE and MORTSHIRE. In The Unstrung Harp, Mr. Earbrass drives to Nether Millstone, where he finds a personalized copy of his second novel 'The Meaning of the House', and later finds copies of his new novel, The Unstrung Harp, in a bookseller's window. Mr. Earbrass lives in Mortshire. Both Nether Millstone and Mortshire are again referred to in Gorey's The Other Statue; the Secrets: Volume One (1968), in a similar manner as in The Unstrung Harp.

By definition, a 'nether millstone' is the lower of the two mill stones in a grain mill. The lower stone is unmoving, and is harder, conjuring the unforgiving part of life which is likewise grinding down both body and soul. Mortshire is where Mr. Earbrass resides in The Unstrung Harp. The fictional Mortshire can be construed to signify death 'mort' and a district 'shire', as in an undesireable location to live.

The Guest: (speculation) Edward, Prince of Wales was often a clandestine visitor to a number of high profile liasons, famously exposed in a 1870 divorce trial as visiting Lady Harriett Mordaunt, while husband Sir Charles Mordaunt was away serving in the House of Commons. He returned home prematurely from a salmon fishing trip to Norway, and discovered his wife Harriett cavorting with Edward on their estate, on two white ponies Sir Charles had earlier acquired from the Prince. Bertie beat a hasty retreat, but an enraged Sir Charles had the two white ponies shot in the presence of his wife, and later had her commited to an insane asylum after she admitted to having several affairs. Prince Edward did not admit to adultery, however, the reputation of the monarchy was severely damaged.

The Invalid: Edward, Prince of Wales was often afflicted, first of typhoid fever in earlier years and later suffering appendicitis just before his accession to the throne. As King, Edward eventually succumbs to severe bronchitis and heart attacks towards the end of his ninth year as monarch, while living in Sandringham House. His poor health was attributed to excessive eating and smoking.

The Lunatic: (speculation) Bertie's favorite brothel in Paris was the wildly luxurious Le Chabanais. There, the Prince had a special chair made which made it easier to enjoy the ladies. It was designed in the Rococo style, as is the stool in Gorey's illustration. Another diversion was to immerse himself and his playmate in a luxurious swan-necked bathtub made of copper, in the style of a Wagnerian swan boat, and filled to the brim with champagne. Salvador Dali later purchased this curio.

The flying onion and boat depicted here named 'Ornate Onion' may be euphemisms for Prince Edward's insatiable and prodigous sexual appetite, in ornate royal garb, as he sails off to Paris. Shakespeare refers to the 'onion' as innuendo of generous sexual equipage.

The Bather: (speculation) Edward, Prince of Wales discovers a message in a bottle, with 'PPC' written upon it. The Prince appears to be relaxing on English shores, with an unexpected bottle possibly drifting across the channel from the Continent. The use of 'PPC', for pour prendre conge, was often used to send a signal of the departure of someone close or familiar. It is part of diplomatic communications protocols which conveys intentions of a message.

Among the many mistresses and affairs Prince Edward engaged in even after his marriage to Princess Alexandra of Denmark, only one seemed to threaten his marriage. Bertie met Daisy Warwick, another British royal, when he was 48. He apparently fell in love with the Countess, who was 20 years younger than he, and their affair lasted a good 10 years. Princess Alexandra left England, to visit family in Denmark, and stayed, ignoring Bertie's pleas for her return. She eventually did in 1899, after Daisy ended her affair with the prince, because she was pregnant from yet another affair. Alexandra was overjoyed at the news, and came home. Bertie was devasted.

The Sybarite: Edward, Prince of Wales, lives a hedonistic lifestyle. As described earlier, he lived the life of Riley whilst in wait, which he most wholeheartedly enjoyed before his accession to the throne, to the dismay of both his family and the public. If 'Victorian England' reflected Queen Victoria's personality: one of sobriety, seriousness and quiet power, 'Edwardian England' was the opposite, reflecting Bertie's taste of having a gusto for life full of relish and with flourish, without regard for propriety.

Sybaris was an ancient city located in southern Italy, and like Pompeii, its inhabitants were known for their conspicuous devotion to pleasure-seeking and opulence.

The Athlete: (speculation) Edward the Prince toured North America when he was 19, and made it a point to visit Harvard University in 1860. It was to become a tradition for visiting royals to drop by the university ever since.

An amusing instance arises when the young Prince requests wine with the planned luncheon held that afternoon, then subsequently requests a beer. Neither could be procured by the school's serving staff, and the transcription of the days events abruptly ended at that point, reports The Harvard Crimson. Perhaps the the young Prince's responses were considered unsuitable for print.

The Watcher: (speculation) Possibly an older Prince of Wales, near his mother's end, or perhaps as newly crowned King Edward VII, sporting a new beard, watches and worries what changes are afoot. The newly crowned king was reportedly very insecure about his prospects for success after the coronation. Note the lack of detail in the window casement. Uncertainty?

The Devotee: Bertie, now King Edward VII, finds redemption as royal patron of the arts, as he uses his new position to support and advance the popularity of the Royal College of Music, bringing enjoyment and appreciation 'which unites the classes' in music and the performing arts.

The backcover illustration: (speculation) Someone, perhaps Edward, Prince of Wales, regarding a new 1900 Coupe, or conversely, Edward is observed driving a new 1900 Coupe.

Andreas Brown had acknowledged that this last illustration, used on the back of the dust jacket, was not part of the original group in The Angel, the Automobilist and Eighteen Others; it was discovered separately. It became the eighteenth illustration, for the sake of this book. Brown also pointed out that he found no obvious order to Gorey's illustrations, as there were no revisions, notes or drafts. It's good to keep that in mind.

Bertie regards the latest 1900 coupe models: a Coupe Renault (vert) and Coupe Docteur de Dion Bouton (rouge). Photo by Glen Emil

In memory of Andreas Brown (1933-2020), in recognition and appreciation for his generous assistance and unwavering support.

Copyright 2020 Goreyography.com. All rights reserved.